Q: How did you begin your journey as an artist?

A: My curiosity with art began in my early childhood. I was constantly creating - painting, drawing, and crafting for hours in my bedroom. When I reached high school, I was accepted into Etobicoke School of the Arts. It was there I received my formal training in the arts, and I'd say my journey really began there.

Q: How has your art evolved? Has your science background had an impact on your art?

A: My art was originally centered around creating colourful pieces with the intention of adding beauty to a space. I worked mainly in acrylics (sometimes oil) that focused on nature and nude figure studies. Over the years my chronic illness unfortunately progressed (I live with a disease known as myalgic encephalomyelitis, ME/CFS for short). In response, I had to adapt to different mediums because of my physical limitations. Collage, photography, makeup art, and sculpture are less labour intensive, and therefore more accessible. What evolved most in my art is the intention behind my work. I still want to create art that is beautiful, but most importantly, I want to use it as a tool for storytelling and raising awareness (for ME/CFS).

I think in not so direct but very profound ways, my science background has impacted my art. The experiences I draw from when creating, are about navigating life in a chronically ill body. For over a decade I was very sick but managed to obtain a BSc in Nutrition and Nutraceutical Sciences and nearly finish an ND degree (naturopathic medical degree). When my illness progressed, there was an overwhelming grief I had to confront when I had to leave the ND program.

My pursuits in nutrition and medicine revealed an undeniable gap. The knowledge and understanding of human physiology and biochemistry in relation to ME/CFS were nowhere to be found. Those answers are not even known by world renowned scientists studying ME/CFS, and somehow I naively believed I could heal myself if I just ate the right foods, took the right supplements, did the right yoga poses, cited the right mantras, etc. It was a painful realization, to know that I had bankrupted my health further in the desperate pursuit of answers to heal/manage my ME/CFS. In this way, my science background indirectly influences my art because my work often touches on a deep grief, heart crushing disappointment, anger, and desperation.

Q: Has the pandemic had an impact on your work, and if so, how?

A: I think the pandemic has definitely impacted my work. It amplifies experiences that were already there to begin with, as someone living with a very marginalized chronic illness. Feelings like grief, isolation, uncertainty of the future, yearning for the way things once were, fear of others (their judgements and ableist comments pre-pandemic; now it's them giving me COVID plus their judgements and ableist comments). These themes have been really central to my work over the past year, and the pandemic has undoubtedly influenced that.

Q: You've worked with a wide variety of media - collage, sculpture, painting, makeup, etc. - what's your favorite medium?

Q: I'm fascinated by your Broken Body/Enduring Spirit sculpture series. You make a powerful statement about learning to connect with your body that also challenges our cultural ideals of productivity. Can you tell me about your inspiration for these sculptures and the process of creating them?

Q: As someone with multiple chronic illnesses, I find much of your work very relatable. Have you found that your art creates a bridge between people living with chronic illness? Any fun stories of how you've connected with others through your art?

A: I'm happy to hear, it means we're not alone in this experience. The only thing worse than going through a difficult time, is feeling like you're the only one going through it. Art definitely creates bridges between those living with chronic illness just for this reason. I know for me, sometimes I haven't fully digested the layers of what I'm going through. If I see a post that really resonates, whether it be writing or art, Im like "ah ha, that's it!" It helps you figure out the root of a feeling you haven't been able to articulate yet. There's healing there too, because it's validation for something you're going through. Validation is so important for those living with ME/CFS, because many of us carry medical trauma from disbelieving physicians, friends, and family members.

My most recent fun connection that I had was from a puzzle makeup look I created for #MillionsMissing this year (#MillionMissing is the annual global protest for myalgic encephalomyelitis). The makeup art was inspired by the book The Puzzle Solver, that tells the story of Ron Davis (director of Stanfords Genome Technology Center) and his family's ongoing battle with their son Whitney Dafoe's severe ME/CFS. I shared it on Twitter, and it reached Tracie White (the author), Janet Dafoe (Whitney's mom) and Whitney. To connect with them on Twitter was a really special moment, because it was a confirmation that my art can have an impact that reaches far beyond the tiny world of my bed.

Q: What's your ultimate goal in sharing your ME/CFS story with others?

A: My ultimate goal is to be seen. I want others to know what it is that I am going through, and the challenges those with ME/CFS face. Our community continues to go through so much, and we need healthy allies and compassion more now than ever. Another goal to sharing my story is to bring healing, comfort, and a sense of community to our experiences. I want to normalize and create discussion around the difficult and challenging struggles we face, both within our bodies, and with the outside world because of them. With cases of long haulers on the rise, there will be some who do not recover, and will go on to develop ME/CFS. Building a stronger unity between each other now will contribute to a stronger foundation for all of our advocacy efforts down the road.

Learn more about Christina's artwork and advocacy - and find out how you can purchase her work - at wordsasmedicine.com.

0 Comments

At my most recent doctor’s appointment, something just seemed off. I was struggling through a bad cold and not thinking clearly, so it didn’t occur to me to ask more questions in the moment. But after I left the office, I found myself thinking, why didn’t he ask me about any of my conditions or symptoms? Why did he ask about specific symptoms I have no history of? When I asked why I needed to come back in six months for another visit, why did he say that he likes to see patients with conditions like depression or headaches more often? (I have no history of either.)

As you can probably imagine, I was frustrated to see such glaring mistakes and inaccuracies in my chart. What if I wind up in the ER, unable to communicate my medical history to the attending physician? God forbid they treat me according to the (mis)information in my chart and potentially cause serious harm. It may sound unlikely, but this happens more than you’d expect. Luckily, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) gives you the right to correct errors in your medical record. While the process for doing so varies from one provider to another, your physician must allow you to request an amendment to your record. They can accept or deny your request, but they must include a record of your request in your file even if it’s denied. For more information about this process and tips for reviewing your records, click here. While this experience has been an unwanted hassle, I’m even more convinced that my research on health literacy (as part of my master’s thesis) is needed now more than ever. Doctors are humans, and we all make mistakes. But by empowering those with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities to hold physicians accountable, maybe we can prevent medical mistakes from harming more patients in the future. Have you had a similar experience? I would love to hear your story. Tell me in the comments or contact me here.

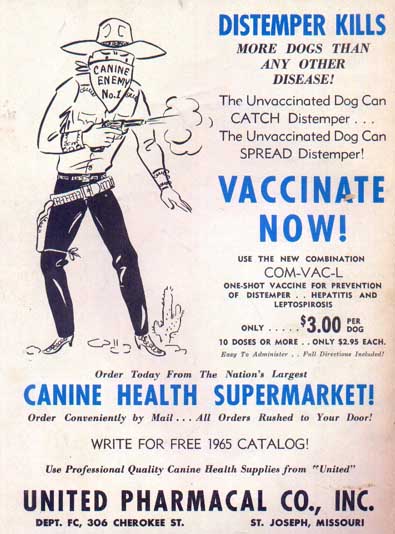

The following essay is a recent assignment for a class I'm currently taking, the Interface of Art and Disease, at the University of Findlay. As more and more Americans receive their COVID-19 vaccinations, the highly publicized debate about the innovative drug’s efficacy continues. While the vaccine was rolled out to the public in record time, its development is based on decades of previous research on similar viral infections and messenger RNA (mRNA). As Krisberg highlights in her article for The Nation’s Health, the challenge of developing an effective vaccine is only the first step in the process of winning the battle against COVID-19. The next – and as some would argue, most important – step in the process is actually getting people vaccinated (6). This may be the biggest challenge yet. Educating the public, and particularly those who are at increased risk of contracting COVID-19, on the benefits and risks of receiving the vaccine is the current priority of health communication professionals. An understanding of the political climate in the United States and other social factors certainly influence the strategies that are used to persuade individuals to roll up their sleeves. But a deeper analysis of the historical underpinnings that surround vaccines in general, and the social implications involved, is necessary to fully grasp the public’s response to the current crisis. By viewing the vaccination dilemma through a health communication lens and using the development of the canine distemper vaccine and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine as examples, I hope to shed light on this pressing public health issue.

The growing popularity of hunting and pet ownership in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain led researchers to begin their investigation into the cause of canine distemper. Early studies sought to isolate and identify the agent responsible for the disease, eventually leading to the development of several experimental vaccines with varying levels of effectiveness. This complex process spurred advances in both animal and human medicine, including the use of ferrets in research (which would prove integral to research on human influenza), new protocols for vaccination and the two-stage vaccine method of immunization (2). Along with new scientific knowledge, distemper research contributed to the development of creative advocacy and funding campaigns that would continue to influence health communication in the coming century. In 1923, the editor of England’s popular magazine The Field established the Field Distemper Fund, allowing the public to participate in an initiative that brought together veterinarians, medical researchers, breeders and various professional associations in the pursuit of a common goal. Advertisements appearing in the magazine encouraged individuals and organizations to contribute to the fund. As a result, over 3,500 donors from around the world became stakeholders in the project. As Bresalier and Worboys point out, “not only did individuals send in donations, but they also followed the progress of the research in popular publications, corresponded with NIMR and WPRL researchers, volunteered pets for trials, and, after 1931, were willing to pay to have their dogs immunized by one of the two methods available” (2). The development of the distemper vaccine highlights a significant shift in public engagement with medical research and the role of communication and health promotion in science and medicine.

Misinformation about the prevalence of HPV and the fear that the vaccine will promote adolescent promiscuity have made some parents hesitant to have their children vaccinated. While the vaccine has been approved for both males and females, the benefits of vaccination are certainly greater for females. This fact, along with the knowledge that HPV can also be prevented through abstinence, has led to a wide range of responses from both adolescents and parents. Engels emphasizes this disparity, citing “a significant gap between parents who are in favor of mandatory TDAP (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) vaccine and those in favor of mandatory HPV vaccine… suggesting that many hold the view that HPV can be avoided through methods other than vaccination” (3). She describes making the vaccine mandatory as a new form of biopower and a strategy of normalization, resulting in a shift in attitudes, behaviors and norms. As health communication professionals work to dispel the myths surrounding the HPV vaccine, they’ve begun to incorporate creative methods of engaging parents and adolescents. For example, researchers at The Ohio State University developed and tested a comic book designed to entertain young people while educating them about the dangers of HPV and the benefits of vaccination (5). While the COVID-19 vaccine and the regulations surrounding it continue to spark controversy in the United States, health communication professionals are tasked with the difficult challenge of not only finding effective ways to share important information, but also influencing individual health behavior on a large scale. In addition to traditional print publications like those used in the fight against canine distemper and even the more recent campaign for HPV vaccination, new tools and technology like social media present new challenges and opportunities to reach the public. The strategic use of these tools could determine the outcome of the current pandemic and pave the way for future advocates in the realm of health literacy. Sources1. Alt, Kimberly | Reviewed By: JoAnna Pendergrass - DVM, K. (2021, March 16). Which dog vaccinations are necessary? Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://www.caninejournal.com/dog-vaccinations/#distemper

2. Bresalier, M., & Worboys, M. (2013, July 5). 'Saving the lives of our dogs': The development of canine distemper vaccine in interwar Britain. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24941736/ 3. Engels, K. S. (2015, October 6). Biopower, normalization, and HPV: A Foucauldian analysis of the HPV vaccine controversy. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26438668/ 4. Grimes, J. (2006, November 03). HPV vaccine development: A case study of prevention and politics. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://iubmb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bmb.2006.49403402148 5. Katz, M. L., Oldach, B. R., Goodwin, J., Reiter, P. L., Ruffin, M. T., IV, & Paskett, E. D. (2014, January 15). Development and initial feedback about a human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine comic book for adolescents. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24420004/ 6. Krisberg, K. (2021, February). Public health messaging vital for COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Nation’s Health, 1–6. The following essay is a recent assignment for a class I'm currently taking, the Interface of Art and Disease, at the University of Findlay. Throughout history, religion and spirituality have played vital roles in the understanding of disease and the practice of medicine. Connections between religious beliefs and disease can be found in almost every culture, and the interplay of science and religion has often led to controversy that has both hindered and spurred medical advancement. Many people turn to faith for a better understanding of the afflictions they experience and an explanation for their pain. This is especially apparent in the case of the infamous Salem witch trials. Founded by the Puritans in 1629, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was established to be a model society, a Christian utopia that would provide the rest of the world with a beacon of Biblical goodness. So when several girls in Salem Village were afflicted with unexplainable symptoms in 1692, the idea that their fits were caused by some form of sin (witchcraft) seemed the obvious conclusion. In the centuries since the Salem witch trials, many theories have emerged in an attempt to explain the unusual events that led to dozens of deaths, ranging from political conflict and economic hardship to Indian raids. More recently, some historians have theorized that an underlying medical cause may be at the root of the afflicted girls’ strange behavior (3). In the 1970s, one researcher proposed ergotism as a possible cause of the Salem girls’ symptoms. Ergot, a fungal disease that affects rye and other crops, is dangerous for humans who consume plants that contain the chemicals produced by the fungus. Ergotism can cause symptoms including tremors, hallucinations, prickling sensations, seizures and muscle spasms. Cool, wet weather and an overreliance on rye as a staple crop have led some historians to believe that many reported episodes of “witchcraft” in Europe may have been triggered by ergot (2). While the symptoms of ergotism certainly parallel the experiences of the afflicted Salem girls, this theory and other medical conditions like meningitis don’t explain some accounts of the girls’ behavior. For example, the victims only exhibited symptoms in the courtroom when they were cued to do so by those in authority (3). Of course, this evidence doesn’t automatically negate a medical cause. Other researchers have argued that the symptoms exhibited in the courtroom could have been the result of trauma or coercion. The societal expectations of girls and women in seventeenth-century New England would have put the young girls, who ranged in age from eleven to twenty, in a position of powerlessness, potentially allowing them to be manipulated or even forced against their will to play the assigned roles as victims of witchcraft (3). Regardless of the root causes that led to the events in Salem, religion played a pivotal role in the way the trials played out. The Salem witch trials are a perfect example of the way religion has been recruited to fill in gaps in science throughout history. Without the knowledge of ergotism and other infectious diseases, the technology needed to properly diagnose physical symptoms or an understanding of the manifestations of psychological trauma, the people of Salem were left with one explanation: witchcraft. Their devout Puritan society naturally concluded that the events they were experiencing stemmed from the sin committed by the “witches” living among them. The notorious episode in Salem is one of many historical examples of the interplay between fanatical religion and society. But what happens when science and religion work together to address disease and public health? The popular BBC drama Call the Midwife, based on the memoirs of midwife Jennifer Worth, depicts the many successes of the partnership between the National Health Service and religious institutions in the East End of London in the 1950s and 1960s. In her commentary on the show, sociology professor Ellen Idler discusses the complexity of the relationship between religion and public health, pointing out that “there is a considerable amount of research showing that higher levels of religious participation in Western countries are associated with lower rates of mortality.” She emphasizes the World Health Organization’s focus on the social determinants of health, arguing that the social capital that a religious institution like Call the Midwife’s Nonnatus House holds in its community plays a vital role in the healthcare and wellbeing of some of London’s most economically-disadvantaged residents (1). In later seasons of Call the Midwife, the still-timely issue of abortion and the ethics surrounding birth control are addressed. The main characters, including the young midwives, the sisters of Nonnatus House, doctors and low-income residents of Poplar, demonstrate the diversity of perspectives on a topic that still causes heated debate today. There is a clear struggle between the religious beliefs of some devout characters and the immediate healthcare needs of others, and this tension serves to highlight the larger existential conflict that characterizes the relationship between religion, science and society. More than half a century later, women’s healthcare and abortion continue to dominate the conversation and raise questions about religion’s role in the public health of a democratic nation. The Salem witch trials and the historical events depicted in Call the Midwife bring attention to the disparate roles that religion has played in health and medicine throughout human history. Arguments can be made that science and religion are two sides of the same coin, yet this view has led to countless deaths and disasters. It has also led to reforms in healthcare that removed barriers, allowing entire populations of disadvantaged people to access care and a better quality of life for the first time. The question of whether religion has been more of a help or a hindrance in the advancement of medicine and the health of populations has no straightforward answer. At every point in history, it has been both. Because the religion of any culture tends to weave its way into the fabric of everyday life, it can’t easily be disentangled from the threads of science, medicine and nature that also sustain us. The interaction of these sometimes contradictory elements can only be acknowledged and commented upon, often with the advantage of hindsight. Of course, the recognition of such relationships doesn’t always lead to answers either, as many survivors of the Salem witch trials realized when they were forced to grapple with difficult questions, like the one Ray addresses in his book: “How could a deeply religious society shed its feelings of guilt after realizing that it was responsible for killing innocent people in the name of God?” (3). While we’re not executing people accused of witchcraft in the US today, I would argue that we’re still wrestling with some of the same questions that plagued villagers in 1692. Sources

1. Idler, E. (2016, April 13). To see how RELIGION boosts public health, WATCH 'call the Midwife' (commentary). Retrieved March 02, 2021, from https://religionnews.com/2016/04/13/call-the-midwife-religion-health-care/ 2. M. Harveson, R. (2017, July 27). Did a Plant Disease Play a Role in the Salem Witch Trials?. Julesburg Advocate (CO). Available from NewsBank: Access World News: https://infoweb-newsbank-com.ezproxy.findlay.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/165EBA002AD17CA0. 3. Ray, B. C. (2017). Satan & Salem: The witch-hunt crisis of 1692. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. As we settle into the cold, dreary winter months following the excitement of the holidays, it’s easy to fall into a slump. Especially as the pandemic rages on and we continue to maintain our social distance. The one thing this time of year is good for? Catching up on some reading! The Book: Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times by Katherine May

While I’m not a sea swimmer, I can relate to the therapeutic experience Katherine describes in the article she wrote for The Outdoor Swimming Society. The story of her relationship with water and her adult diagnosis of autism are inseparable. She even gives us a glimpse into her winter of hospital visits and diagnostic tests as she awaits an explanation for her persistent abdominal pain. Of course illness is only one manifestation of winter, but it certainly demands its share of rest and retreat. As Katherine puts it, “winter is asking me to be more careful with my energies and to rest a while until spring.” Some would say the world is enduring a collective winter of sorts at the moment. And while we anxiously await the spring, the best prescription for our wintering souls may be this book, a hot cup of tea and a warm blanket. The Tea: Savoy Tea Company's Frosted Orange Roll Tea

If you enjoyed the book, check out Katherine’s podcast The Wintering Sessions.

|

My name is Maggie Morehart, and I'm the creator of Incurable. Learn more.

Categories

All

More Places to Find Me |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed