|

The following essay is a recent assignment for a class I'm currently taking, the Interface of Art and Disease, at the University of Findlay. As more and more Americans receive their COVID-19 vaccinations, the highly publicized debate about the innovative drug’s efficacy continues. While the vaccine was rolled out to the public in record time, its development is based on decades of previous research on similar viral infections and messenger RNA (mRNA). As Krisberg highlights in her article for The Nation’s Health, the challenge of developing an effective vaccine is only the first step in the process of winning the battle against COVID-19. The next – and as some would argue, most important – step in the process is actually getting people vaccinated (6). This may be the biggest challenge yet. Educating the public, and particularly those who are at increased risk of contracting COVID-19, on the benefits and risks of receiving the vaccine is the current priority of health communication professionals. An understanding of the political climate in the United States and other social factors certainly influence the strategies that are used to persuade individuals to roll up their sleeves. But a deeper analysis of the historical underpinnings that surround vaccines in general, and the social implications involved, is necessary to fully grasp the public’s response to the current crisis. By viewing the vaccination dilemma through a health communication lens and using the development of the canine distemper vaccine and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine as examples, I hope to shed light on this pressing public health issue.

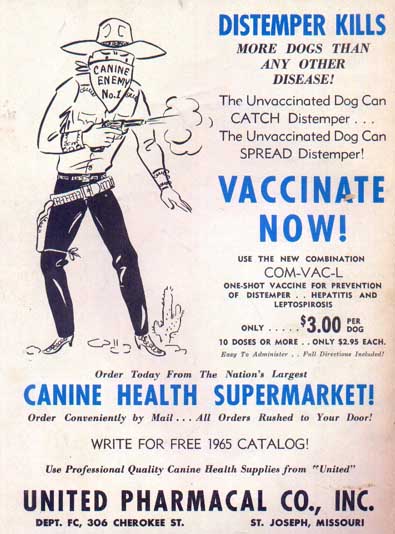

The growing popularity of hunting and pet ownership in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain led researchers to begin their investigation into the cause of canine distemper. Early studies sought to isolate and identify the agent responsible for the disease, eventually leading to the development of several experimental vaccines with varying levels of effectiveness. This complex process spurred advances in both animal and human medicine, including the use of ferrets in research (which would prove integral to research on human influenza), new protocols for vaccination and the two-stage vaccine method of immunization (2). Along with new scientific knowledge, distemper research contributed to the development of creative advocacy and funding campaigns that would continue to influence health communication in the coming century. In 1923, the editor of England’s popular magazine The Field established the Field Distemper Fund, allowing the public to participate in an initiative that brought together veterinarians, medical researchers, breeders and various professional associations in the pursuit of a common goal. Advertisements appearing in the magazine encouraged individuals and organizations to contribute to the fund. As a result, over 3,500 donors from around the world became stakeholders in the project. As Bresalier and Worboys point out, “not only did individuals send in donations, but they also followed the progress of the research in popular publications, corresponded with NIMR and WPRL researchers, volunteered pets for trials, and, after 1931, were willing to pay to have their dogs immunized by one of the two methods available” (2). The development of the distemper vaccine highlights a significant shift in public engagement with medical research and the role of communication and health promotion in science and medicine.

Misinformation about the prevalence of HPV and the fear that the vaccine will promote adolescent promiscuity have made some parents hesitant to have their children vaccinated. While the vaccine has been approved for both males and females, the benefits of vaccination are certainly greater for females. This fact, along with the knowledge that HPV can also be prevented through abstinence, has led to a wide range of responses from both adolescents and parents. Engels emphasizes this disparity, citing “a significant gap between parents who are in favor of mandatory TDAP (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) vaccine and those in favor of mandatory HPV vaccine… suggesting that many hold the view that HPV can be avoided through methods other than vaccination” (3). She describes making the vaccine mandatory as a new form of biopower and a strategy of normalization, resulting in a shift in attitudes, behaviors and norms. As health communication professionals work to dispel the myths surrounding the HPV vaccine, they’ve begun to incorporate creative methods of engaging parents and adolescents. For example, researchers at The Ohio State University developed and tested a comic book designed to entertain young people while educating them about the dangers of HPV and the benefits of vaccination (5). While the COVID-19 vaccine and the regulations surrounding it continue to spark controversy in the United States, health communication professionals are tasked with the difficult challenge of not only finding effective ways to share important information, but also influencing individual health behavior on a large scale. In addition to traditional print publications like those used in the fight against canine distemper and even the more recent campaign for HPV vaccination, new tools and technology like social media present new challenges and opportunities to reach the public. The strategic use of these tools could determine the outcome of the current pandemic and pave the way for future advocates in the realm of health literacy. Sources1. Alt, Kimberly | Reviewed By: JoAnna Pendergrass - DVM, K. (2021, March 16). Which dog vaccinations are necessary? Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://www.caninejournal.com/dog-vaccinations/#distemper

2. Bresalier, M., & Worboys, M. (2013, July 5). 'Saving the lives of our dogs': The development of canine distemper vaccine in interwar Britain. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24941736/ 3. Engels, K. S. (2015, October 6). Biopower, normalization, and HPV: A Foucauldian analysis of the HPV vaccine controversy. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26438668/ 4. Grimes, J. (2006, November 03). HPV vaccine development: A case study of prevention and politics. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://iubmb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bmb.2006.49403402148 5. Katz, M. L., Oldach, B. R., Goodwin, J., Reiter, P. L., Ruffin, M. T., IV, & Paskett, E. D. (2014, January 15). Development and initial feedback about a human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine comic book for adolescents. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24420004/ 6. Krisberg, K. (2021, February). Public health messaging vital for COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Nation’s Health, 1–6.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

My name is Maggie Morehart, and I'm the creator of Incurable. Learn more.

Categories

All

More Places to Find Me |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed