|

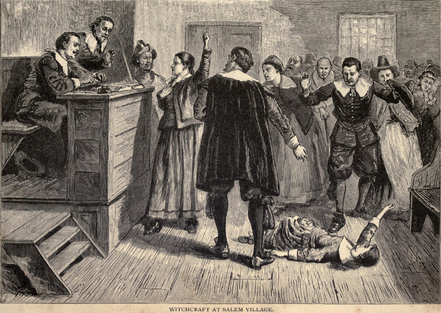

The following essay is a recent assignment for a class I'm currently taking, the Interface of Art and Disease, at the University of Findlay. Throughout history, religion and spirituality have played vital roles in the understanding of disease and the practice of medicine. Connections between religious beliefs and disease can be found in almost every culture, and the interplay of science and religion has often led to controversy that has both hindered and spurred medical advancement. Many people turn to faith for a better understanding of the afflictions they experience and an explanation for their pain. This is especially apparent in the case of the infamous Salem witch trials. Founded by the Puritans in 1629, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was established to be a model society, a Christian utopia that would provide the rest of the world with a beacon of Biblical goodness. So when several girls in Salem Village were afflicted with unexplainable symptoms in 1692, the idea that their fits were caused by some form of sin (witchcraft) seemed the obvious conclusion. In the centuries since the Salem witch trials, many theories have emerged in an attempt to explain the unusual events that led to dozens of deaths, ranging from political conflict and economic hardship to Indian raids. More recently, some historians have theorized that an underlying medical cause may be at the root of the afflicted girls’ strange behavior (3). In the 1970s, one researcher proposed ergotism as a possible cause of the Salem girls’ symptoms. Ergot, a fungal disease that affects rye and other crops, is dangerous for humans who consume plants that contain the chemicals produced by the fungus. Ergotism can cause symptoms including tremors, hallucinations, prickling sensations, seizures and muscle spasms. Cool, wet weather and an overreliance on rye as a staple crop have led some historians to believe that many reported episodes of “witchcraft” in Europe may have been triggered by ergot (2). While the symptoms of ergotism certainly parallel the experiences of the afflicted Salem girls, this theory and other medical conditions like meningitis don’t explain some accounts of the girls’ behavior. For example, the victims only exhibited symptoms in the courtroom when they were cued to do so by those in authority (3). Of course, this evidence doesn’t automatically negate a medical cause. Other researchers have argued that the symptoms exhibited in the courtroom could have been the result of trauma or coercion. The societal expectations of girls and women in seventeenth-century New England would have put the young girls, who ranged in age from eleven to twenty, in a position of powerlessness, potentially allowing them to be manipulated or even forced against their will to play the assigned roles as victims of witchcraft (3). Regardless of the root causes that led to the events in Salem, religion played a pivotal role in the way the trials played out. The Salem witch trials are a perfect example of the way religion has been recruited to fill in gaps in science throughout history. Without the knowledge of ergotism and other infectious diseases, the technology needed to properly diagnose physical symptoms or an understanding of the manifestations of psychological trauma, the people of Salem were left with one explanation: witchcraft. Their devout Puritan society naturally concluded that the events they were experiencing stemmed from the sin committed by the “witches” living among them. The notorious episode in Salem is one of many historical examples of the interplay between fanatical religion and society. But what happens when science and religion work together to address disease and public health? The popular BBC drama Call the Midwife, based on the memoirs of midwife Jennifer Worth, depicts the many successes of the partnership between the National Health Service and religious institutions in the East End of London in the 1950s and 1960s. In her commentary on the show, sociology professor Ellen Idler discusses the complexity of the relationship between religion and public health, pointing out that “there is a considerable amount of research showing that higher levels of religious participation in Western countries are associated with lower rates of mortality.” She emphasizes the World Health Organization’s focus on the social determinants of health, arguing that the social capital that a religious institution like Call the Midwife’s Nonnatus House holds in its community plays a vital role in the healthcare and wellbeing of some of London’s most economically-disadvantaged residents (1). In later seasons of Call the Midwife, the still-timely issue of abortion and the ethics surrounding birth control are addressed. The main characters, including the young midwives, the sisters of Nonnatus House, doctors and low-income residents of Poplar, demonstrate the diversity of perspectives on a topic that still causes heated debate today. There is a clear struggle between the religious beliefs of some devout characters and the immediate healthcare needs of others, and this tension serves to highlight the larger existential conflict that characterizes the relationship between religion, science and society. More than half a century later, women’s healthcare and abortion continue to dominate the conversation and raise questions about religion’s role in the public health of a democratic nation. The Salem witch trials and the historical events depicted in Call the Midwife bring attention to the disparate roles that religion has played in health and medicine throughout human history. Arguments can be made that science and religion are two sides of the same coin, yet this view has led to countless deaths and disasters. It has also led to reforms in healthcare that removed barriers, allowing entire populations of disadvantaged people to access care and a better quality of life for the first time. The question of whether religion has been more of a help or a hindrance in the advancement of medicine and the health of populations has no straightforward answer. At every point in history, it has been both. Because the religion of any culture tends to weave its way into the fabric of everyday life, it can’t easily be disentangled from the threads of science, medicine and nature that also sustain us. The interaction of these sometimes contradictory elements can only be acknowledged and commented upon, often with the advantage of hindsight. Of course, the recognition of such relationships doesn’t always lead to answers either, as many survivors of the Salem witch trials realized when they were forced to grapple with difficult questions, like the one Ray addresses in his book: “How could a deeply religious society shed its feelings of guilt after realizing that it was responsible for killing innocent people in the name of God?” (3). While we’re not executing people accused of witchcraft in the US today, I would argue that we’re still wrestling with some of the same questions that plagued villagers in 1692. Sources

1. Idler, E. (2016, April 13). To see how RELIGION boosts public health, WATCH 'call the Midwife' (commentary). Retrieved March 02, 2021, from https://religionnews.com/2016/04/13/call-the-midwife-religion-health-care/ 2. M. Harveson, R. (2017, July 27). Did a Plant Disease Play a Role in the Salem Witch Trials?. Julesburg Advocate (CO). Available from NewsBank: Access World News: https://infoweb-newsbank-com.ezproxy.findlay.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/165EBA002AD17CA0. 3. Ray, B. C. (2017). Satan & Salem: The witch-hunt crisis of 1692. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

My name is Maggie Morehart, and I'm the creator of Incurable. Learn more.

Categories

All

More Places to Find Me |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed