|

July is Disability Pride Month! To celebrate, I'll be sharing work by some of my favorite artists and advocates this month.

In April, I presented a poster project titled Visual / Virtual / Viral: Communicating Disease and Disability Experience Through Art in the Digital Age at the University of Findlay's Symposium for Scholarship and Creativity. My interactive poster won the Academic Excellence Poster Prize and was accepted into the Midwest Popular Culture Association's annual conference, where I'll be presenting additional research in October. In this presentation, I explore the work of artists like Elizabeth Jameson, who reclaims her own medical data by creating colorful portraits from her MRI scans. Other artists, like Emma Jones, have launched movements that encourage the participation of people with chronic illnesses around the world. These movements continue to grow online and off, with craftsmen like Evan Hebenstreit merging the traditional art of woodcarving with an international awareness campaign. Explore more works by these talented artists by clicking on the images below. And keep an eye out for additional featured artists this month!

0 Comments

I recently stumbled across Emilie Wapnick’s Tedx Talk Why Some of Us Don’t Have One True Calling, and in twelve short minutes, my entire outlook on life changed. Okay, that may be an exaggeration, but it really forced me to reflect on my choices, habits and interests in a new way. It also introduced me to a word I’d never heard before and one that I identified with immediately: multipotentialite.

According to Emilie, a multipotentialite is someone with many interests and creative pursuits.

Just having a name for a defining element of my personality gave me a tangible sense of relief, a bit like the feeling you get when you finally receive a diagnosis after being sick for months or years. Naturally, I wanted to know more about this “diagnosis,” so I visited Emilie’s website, ordered her book (and a few other related titles) on Amazon and dove headfirst down a YouTube rabbit hole of multipotentiality. I consequently realized that I was exhibiting classic symptoms of multipotentiality in my search for more information on multipotentiality, the irony of which was not lost on me.

As I begin to think about the many ways my multipod (short-hand for multipotentialite) personality has manifested in my life, one of my first observations is the way I tend to thrive with multiple part-time jobs. The times in my life when I’ve felt the happiest and most fulfilled in my work have been when I’m not working a single, full-time gig but several wildly different ones at once. As they say, variety is the spice of life. And it can also be the spice of your work life! Coincidentally, flexible schedules, shorter shifts and the ability to work in various different environments act as coping mechanisms that help me to manage multiple chronic illnesses too. (Because what kind of multipod would I be if I didn’t also have multiple chronic illnesses?)

As I continued to reflect, so many things in both my work and personal life began to make sense – like my long-time obsession with George Washington Carver (perhaps the greatest multipotentialite of all time), the siren call of Hobby Lobby, my interest in duathlon (why choose when you can run and bike?) or all the headaches I caused my freshman Career Exploration instructor in college.

As incompatible as these two identities may seem – how can you focus on so many different things when just managing your illness can seem like a full-time job? – the more I reflect on this newfound label, the more benefits I see to being a multipod with chronic illness. Juggling all these diverse interests over the years has certainly allowed me to practice some of the skills needed to juggle symptoms, medications and doctors. It allowed me to pivot in my career when my demanding full-time leadership role took its toll on my health. And it’s allowing me to make connections between seemingly unrelated topics like chronic illness and art, health and literacy and communication and disability.

Many of the downsides to being a chronically ill multipod, like feeling flakey or pushing past your physical limits, are accompanied by tremendous upsides. It’s certainly frustrating when your body can’t keep up with your wide range of interests and pursuits, but if one passion turns out to be too physically demanding, there are a dozen others to fall back on. While other folks struggled with boredom during last year’s quarantine, I finally made some progress on the many projects I’d been anxiously waiting to dive into.

After 33 years as a multipod, I finally have a word for the unique and sometimes chaotic way my brain works. My fellow spoonies will understand how empowering something as simple as a name can be.

Are you a multipotentialite with chronic illness or disability? I would love to hear from you! Leave a comment or contact me here. At my most recent doctor’s appointment, something just seemed off. I was struggling through a bad cold and not thinking clearly, so it didn’t occur to me to ask more questions in the moment. But after I left the office, I found myself thinking, why didn’t he ask me about any of my conditions or symptoms? Why did he ask about specific symptoms I have no history of? When I asked why I needed to come back in six months for another visit, why did he say that he likes to see patients with conditions like depression or headaches more often? (I have no history of either.)

As you can probably imagine, I was frustrated to see such glaring mistakes and inaccuracies in my chart. What if I wind up in the ER, unable to communicate my medical history to the attending physician? God forbid they treat me according to the (mis)information in my chart and potentially cause serious harm. It may sound unlikely, but this happens more than you’d expect. Luckily, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) gives you the right to correct errors in your medical record. While the process for doing so varies from one provider to another, your physician must allow you to request an amendment to your record. They can accept or deny your request, but they must include a record of your request in your file even if it’s denied. For more information about this process and tips for reviewing your records, click here. While this experience has been an unwanted hassle, I’m even more convinced that my research on health literacy (as part of my master’s thesis) is needed now more than ever. Doctors are humans, and we all make mistakes. But by empowering those with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities to hold physicians accountable, maybe we can prevent medical mistakes from harming more patients in the future. Have you had a similar experience? I would love to hear your story. Tell me in the comments or contact me here.

The following essay is a recent assignment for a class I'm currently taking, the Interface of Art and Disease, at the University of Findlay. As more and more Americans receive their COVID-19 vaccinations, the highly publicized debate about the innovative drug’s efficacy continues. While the vaccine was rolled out to the public in record time, its development is based on decades of previous research on similar viral infections and messenger RNA (mRNA). As Krisberg highlights in her article for The Nation’s Health, the challenge of developing an effective vaccine is only the first step in the process of winning the battle against COVID-19. The next – and as some would argue, most important – step in the process is actually getting people vaccinated (6). This may be the biggest challenge yet. Educating the public, and particularly those who are at increased risk of contracting COVID-19, on the benefits and risks of receiving the vaccine is the current priority of health communication professionals. An understanding of the political climate in the United States and other social factors certainly influence the strategies that are used to persuade individuals to roll up their sleeves. But a deeper analysis of the historical underpinnings that surround vaccines in general, and the social implications involved, is necessary to fully grasp the public’s response to the current crisis. By viewing the vaccination dilemma through a health communication lens and using the development of the canine distemper vaccine and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine as examples, I hope to shed light on this pressing public health issue.

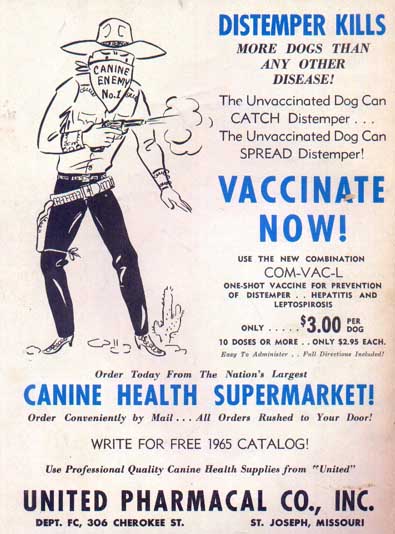

The growing popularity of hunting and pet ownership in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain led researchers to begin their investigation into the cause of canine distemper. Early studies sought to isolate and identify the agent responsible for the disease, eventually leading to the development of several experimental vaccines with varying levels of effectiveness. This complex process spurred advances in both animal and human medicine, including the use of ferrets in research (which would prove integral to research on human influenza), new protocols for vaccination and the two-stage vaccine method of immunization (2). Along with new scientific knowledge, distemper research contributed to the development of creative advocacy and funding campaigns that would continue to influence health communication in the coming century. In 1923, the editor of England’s popular magazine The Field established the Field Distemper Fund, allowing the public to participate in an initiative that brought together veterinarians, medical researchers, breeders and various professional associations in the pursuit of a common goal. Advertisements appearing in the magazine encouraged individuals and organizations to contribute to the fund. As a result, over 3,500 donors from around the world became stakeholders in the project. As Bresalier and Worboys point out, “not only did individuals send in donations, but they also followed the progress of the research in popular publications, corresponded with NIMR and WPRL researchers, volunteered pets for trials, and, after 1931, were willing to pay to have their dogs immunized by one of the two methods available” (2). The development of the distemper vaccine highlights a significant shift in public engagement with medical research and the role of communication and health promotion in science and medicine.

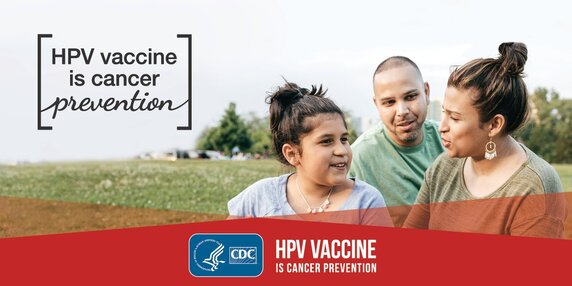

Misinformation about the prevalence of HPV and the fear that the vaccine will promote adolescent promiscuity have made some parents hesitant to have their children vaccinated. While the vaccine has been approved for both males and females, the benefits of vaccination are certainly greater for females. This fact, along with the knowledge that HPV can also be prevented through abstinence, has led to a wide range of responses from both adolescents and parents. Engels emphasizes this disparity, citing “a significant gap between parents who are in favor of mandatory TDAP (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) vaccine and those in favor of mandatory HPV vaccine… suggesting that many hold the view that HPV can be avoided through methods other than vaccination” (3). She describes making the vaccine mandatory as a new form of biopower and a strategy of normalization, resulting in a shift in attitudes, behaviors and norms. As health communication professionals work to dispel the myths surrounding the HPV vaccine, they’ve begun to incorporate creative methods of engaging parents and adolescents. For example, researchers at The Ohio State University developed and tested a comic book designed to entertain young people while educating them about the dangers of HPV and the benefits of vaccination (5). While the COVID-19 vaccine and the regulations surrounding it continue to spark controversy in the United States, health communication professionals are tasked with the difficult challenge of not only finding effective ways to share important information, but also influencing individual health behavior on a large scale. In addition to traditional print publications like those used in the fight against canine distemper and even the more recent campaign for HPV vaccination, new tools and technology like social media present new challenges and opportunities to reach the public. The strategic use of these tools could determine the outcome of the current pandemic and pave the way for future advocates in the realm of health literacy. Sources1. Alt, Kimberly | Reviewed By: JoAnna Pendergrass - DVM, K. (2021, March 16). Which dog vaccinations are necessary? Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://www.caninejournal.com/dog-vaccinations/#distemper

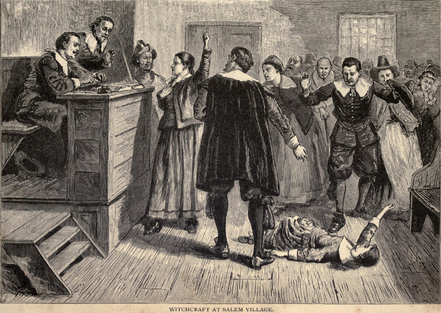

2. Bresalier, M., & Worboys, M. (2013, July 5). 'Saving the lives of our dogs': The development of canine distemper vaccine in interwar Britain. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24941736/ 3. Engels, K. S. (2015, October 6). Biopower, normalization, and HPV: A Foucauldian analysis of the HPV vaccine controversy. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26438668/ 4. Grimes, J. (2006, November 03). HPV vaccine development: A case study of prevention and politics. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://iubmb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bmb.2006.49403402148 5. Katz, M. L., Oldach, B. R., Goodwin, J., Reiter, P. L., Ruffin, M. T., IV, & Paskett, E. D. (2014, January 15). Development and initial feedback about a human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine comic book for adolescents. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24420004/ 6. Krisberg, K. (2021, February). Public health messaging vital for COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Nation’s Health, 1–6. The following essay is a recent assignment for a class I'm currently taking, the Interface of Art and Disease, at the University of Findlay. Throughout history, religion and spirituality have played vital roles in the understanding of disease and the practice of medicine. Connections between religious beliefs and disease can be found in almost every culture, and the interplay of science and religion has often led to controversy that has both hindered and spurred medical advancement. Many people turn to faith for a better understanding of the afflictions they experience and an explanation for their pain. This is especially apparent in the case of the infamous Salem witch trials. Founded by the Puritans in 1629, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was established to be a model society, a Christian utopia that would provide the rest of the world with a beacon of Biblical goodness. So when several girls in Salem Village were afflicted with unexplainable symptoms in 1692, the idea that their fits were caused by some form of sin (witchcraft) seemed the obvious conclusion. In the centuries since the Salem witch trials, many theories have emerged in an attempt to explain the unusual events that led to dozens of deaths, ranging from political conflict and economic hardship to Indian raids. More recently, some historians have theorized that an underlying medical cause may be at the root of the afflicted girls’ strange behavior (3). In the 1970s, one researcher proposed ergotism as a possible cause of the Salem girls’ symptoms. Ergot, a fungal disease that affects rye and other crops, is dangerous for humans who consume plants that contain the chemicals produced by the fungus. Ergotism can cause symptoms including tremors, hallucinations, prickling sensations, seizures and muscle spasms. Cool, wet weather and an overreliance on rye as a staple crop have led some historians to believe that many reported episodes of “witchcraft” in Europe may have been triggered by ergot (2). While the symptoms of ergotism certainly parallel the experiences of the afflicted Salem girls, this theory and other medical conditions like meningitis don’t explain some accounts of the girls’ behavior. For example, the victims only exhibited symptoms in the courtroom when they were cued to do so by those in authority (3). Of course, this evidence doesn’t automatically negate a medical cause. Other researchers have argued that the symptoms exhibited in the courtroom could have been the result of trauma or coercion. The societal expectations of girls and women in seventeenth-century New England would have put the young girls, who ranged in age from eleven to twenty, in a position of powerlessness, potentially allowing them to be manipulated or even forced against their will to play the assigned roles as victims of witchcraft (3). Regardless of the root causes that led to the events in Salem, religion played a pivotal role in the way the trials played out. The Salem witch trials are a perfect example of the way religion has been recruited to fill in gaps in science throughout history. Without the knowledge of ergotism and other infectious diseases, the technology needed to properly diagnose physical symptoms or an understanding of the manifestations of psychological trauma, the people of Salem were left with one explanation: witchcraft. Their devout Puritan society naturally concluded that the events they were experiencing stemmed from the sin committed by the “witches” living among them. The notorious episode in Salem is one of many historical examples of the interplay between fanatical religion and society. But what happens when science and religion work together to address disease and public health? The popular BBC drama Call the Midwife, based on the memoirs of midwife Jennifer Worth, depicts the many successes of the partnership between the National Health Service and religious institutions in the East End of London in the 1950s and 1960s. In her commentary on the show, sociology professor Ellen Idler discusses the complexity of the relationship between religion and public health, pointing out that “there is a considerable amount of research showing that higher levels of religious participation in Western countries are associated with lower rates of mortality.” She emphasizes the World Health Organization’s focus on the social determinants of health, arguing that the social capital that a religious institution like Call the Midwife’s Nonnatus House holds in its community plays a vital role in the healthcare and wellbeing of some of London’s most economically-disadvantaged residents (1). In later seasons of Call the Midwife, the still-timely issue of abortion and the ethics surrounding birth control are addressed. The main characters, including the young midwives, the sisters of Nonnatus House, doctors and low-income residents of Poplar, demonstrate the diversity of perspectives on a topic that still causes heated debate today. There is a clear struggle between the religious beliefs of some devout characters and the immediate healthcare needs of others, and this tension serves to highlight the larger existential conflict that characterizes the relationship between religion, science and society. More than half a century later, women’s healthcare and abortion continue to dominate the conversation and raise questions about religion’s role in the public health of a democratic nation. The Salem witch trials and the historical events depicted in Call the Midwife bring attention to the disparate roles that religion has played in health and medicine throughout human history. Arguments can be made that science and religion are two sides of the same coin, yet this view has led to countless deaths and disasters. It has also led to reforms in healthcare that removed barriers, allowing entire populations of disadvantaged people to access care and a better quality of life for the first time. The question of whether religion has been more of a help or a hindrance in the advancement of medicine and the health of populations has no straightforward answer. At every point in history, it has been both. Because the religion of any culture tends to weave its way into the fabric of everyday life, it can’t easily be disentangled from the threads of science, medicine and nature that also sustain us. The interaction of these sometimes contradictory elements can only be acknowledged and commented upon, often with the advantage of hindsight. Of course, the recognition of such relationships doesn’t always lead to answers either, as many survivors of the Salem witch trials realized when they were forced to grapple with difficult questions, like the one Ray addresses in his book: “How could a deeply religious society shed its feelings of guilt after realizing that it was responsible for killing innocent people in the name of God?” (3). While we’re not executing people accused of witchcraft in the US today, I would argue that we’re still wrestling with some of the same questions that plagued villagers in 1692. Sources

1. Idler, E. (2016, April 13). To see how RELIGION boosts public health, WATCH 'call the Midwife' (commentary). Retrieved March 02, 2021, from https://religionnews.com/2016/04/13/call-the-midwife-religion-health-care/ 2. M. Harveson, R. (2017, July 27). Did a Plant Disease Play a Role in the Salem Witch Trials?. Julesburg Advocate (CO). Available from NewsBank: Access World News: https://infoweb-newsbank-com.ezproxy.findlay.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/165EBA002AD17CA0. 3. Ray, B. C. (2017). Satan & Salem: The witch-hunt crisis of 1692. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. |

My name is Maggie Morehart, and I'm the creator of Incurable. Learn more.

Categories

All

More Places to Find Me |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed